The prime time to arrive at Trethowan Brothers Dairy at Puxton Court Farm in Somerset is a little before 7am when the morning’s milk goes into the vat, signalling the start of the Pitchfork Cheddar make. The Gorwydd Caerphilly made a few days earlier is fished from its brine bath and shelved in the maturing room, making space for a day of cheddaring. The small team has welcomed us into the dairy with open, well-scrubbed arms to lend a hand with the whole process.

Todd Trethowan started making Caerphilly at his family farm ‘Gorwydd’ in Ceredigion, West Wales in the mid-90s, following an apprenticeship with Chris Duckett in Somerset, the only traditional Caerphilly maker in the UK at the time. Todd’s brother Maugan joined him, and from their tiny vat they produced just four wheels of Gorwydd Caerphilly at a time. They then upgraded to a larger vat that, it transpired, wouldn’t fit through the doors. Thankfully knocking down a portion of the wall to install it was all worth it, as the cheese proved delicious and increasingly popular. The brothers outgrew the family farm and began to look for a new dairy. They experimented with lots of different milk from a whole host of farms, before selecting a source from a single herd of Holstein Friesian and Jersey cows at Puxton Court Farm, five miles from the village Cheddar. They were led by the milk; the milk is the thing. As involved as cheesemaking is, it comes down to letting the cheese express the quality and flavour of the milk.

Being so close to Cheddar, the brothers knew they had to have a go at making the namesake cheese. This in many ways was risky, as they wouldn’t find out the true result of each batch until a year or more later – this is the genuine slow food movement after all. There’s a tradition of Cheddar makers producing Caerphilly as a secondary cheese, as it’s a faster process, reaches maturity much more quickly, and is therefore more profitable. The brothers continue this tradition, albeit coming at it from the other way around. However, the risk paid off with their award-winning Pitchfork Cheddar. And we can see why after a day in the dairy. Handmade doesn’t cover it: this is full body made, involving a great deal of physical work alongside scientific precision. From hairnet to wellies via shin-length waterproof aprons, the top to toe kit denotes the labour we’re in for.

The starter culture is added to the vat of unpasteurised morning milk, followed by the liquid solution of rennet, both at intervals dictated by meticulous monitoring of temperature. We all sip that morning’s starter culture mix, and bets are placed for how long the make will be. It’s a skill these cheesemakers have developed to help them judge how this day’s milk may need to be worked, but it’s also a decent predicter for whether their tea break later will be five minutes or if it will stretch to ten. The starter makes for a fortifying breakfast drink.

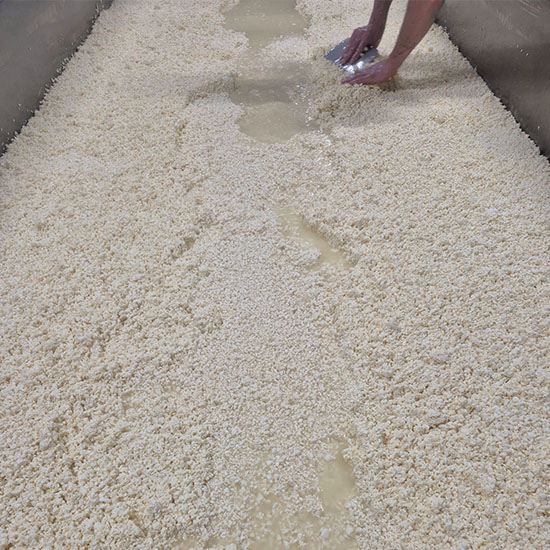

Once the curds are cut, by a machine moving in mesmerising concentric circles, both the curds and whey pass into a draining vat through a gentle piping system to keep the curds intact. We taste the finely cut pre-salted curds, reminiscent of panna cotta or junket, with a slight sweetness and soft squeakiness. When the whey has drained away, the hard work begins: cutting, flipping and stacking the cut slabs of coagulating curd, starting small then piling high, the towers slumping over, cheese forming under its own weight. This is the part of the process known as ‘cheddaring’. The cheesemakers consistently test the acidity between each stacking session, calculating how long to wait before we go again. We settle into a flow of patient waiting and flying into action according to the clock. A curd-block slides down the vat at speed, spraying residual whey in my face – no doubt very good for the skin. When the piled blocks have formed an almost meat-like muscled texture, we hand-hoist and feed them into the milling machine, adding pre-measured salt to the resulting chopped curds. It’s at this point the pitchforks come out, giving this cheddar its name and adding a vigorous drama to proceedings. Forking in the salt and bringing down the temperature is bracing work and curds fly. We help shovel and weigh these into prepped moulds which are then tightly stacked horizontally to press overnight.

With industrial processed Cheddar, you’re looking at one enormous vat that takes up a whole room, churning out homogenous blocks and wheels, and earning handmade accreditation if the pressed curds are turned just one single time by hand during the process. The makers will certainly be less exhausted by the day’s end, but much less richly rewarded.

Good things come to those who wait, and traditional Cheddar maturation means months of patience. Though this is not a passive act. Shelving the heavy cheeses on the ceiling-skimming boards in carefully monitored conditions, then turning them all by hand at logged intervals, is not for the faint-hearted. A new maturing wing of the dairy had to be built to house the tonnes of Pitchfork. And though they’re smaller and younger, the dozens of Caerphilly wheels need frequent flipping and rub downs. Hop on stepladders for the top shelves and bend low for the bottom, all at a slick yet methodical pace.

We leave with a renewed appreciation for the hard work, expertise and care that goes into the cheese we enjoy so much – as well as some milled curds which were set aside after the pitchforking for us to take home. These are destined for poutine very literally from scratch. Delicious.